Michael Burry On Why Private Investors Outperform

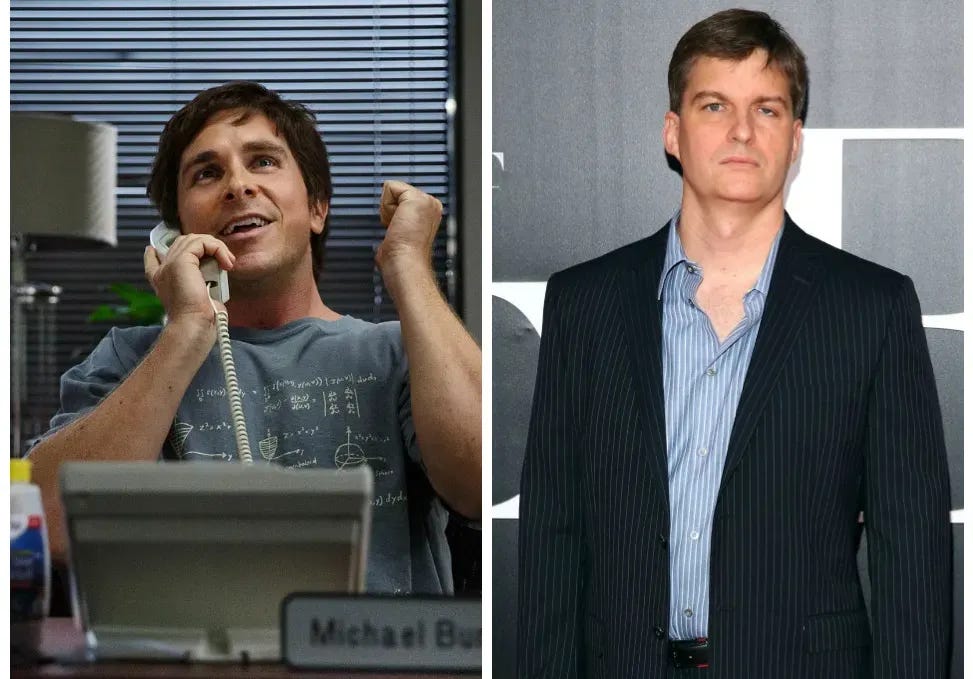

Michael Burry, the founder of Scion Asset Management, gained widespread recognition for his bet against the U.S. housing market before the 2008 financial crisis. He became a household name after hew was played by Christian Bale in the movie ‘The Big Short”. Known for his contrarian approach and willingness to endure significant criticism while his theses play out, Burry has become one of the most closely watched figures in investing.

Michael Burry recently reflected on the challenges of running a public, transparent portfolio versus a private “black box” one. He argues transparency in investment management actually harms returns. His thesis centers on how public disclosure fundamentally changes investor behavior in ways that undermine long-term compounding.

Social Media Criticism

Burry contends that critics of public portfolios rarely engage with the underlying research in any meaningful way. Instead of careful analysis, fund managers face a barrage of reactive commentary. Every disclosed position becomes fodder for instant judgment:

Any position that looks like an “obvious loser” (a stock or asset that’s declining).

Any “obvious winner” the fund doesn’t own (something that’s surging).

This criticism can be harsh, widespread, and viral in today’s social media environment. The pressure is intense because the portfolio is fully exposed.

Black Box Advantage

Managers who keep their strategies and positions completely private (“black box”) avoid this scrutiny. Burry argues this secrecy allows them to take bold, long-term bets without fear of immediate backlash. Examples given:

Jim Simons’ Renaissance Technologies famously averaged ~50% annual returns for years because no one knew what they were doing.

Individual private investors can also compound at very high rates (even 50% a year) when no one is watching.

In contrast, few managers consistently hit those kinds of numbers once they have to disclose positions regularly.

Transparency Changes Strategy

When managers are exposed to constant judgment, they tend to abandon deep, fundamental long-term investing. Instead, they shift to:

Short-term trading.

Momentum strategies.

Technical signals.

“Pod” structures (small, semi-independent trading teams focused on beating benchmarks every quarter).

These approaches can produce strong returns for brief periods, but they rarely sustain the exceptional long-term compounding that private or black-box managers can achieve.

Transparency sounds good in theory, but in practice it creates strong incentives for caution, short-termism, and crowd-following behavior. The highest long-term returns have historically come from managers who could operate in private, free from the noise and pressure of constant public criticism.

Where We Agree With Burry

The central point that transparency creates intense short-term pressure that discourages bold, patient, contrarian fundamental investing is well-supported by both historical evidence and behavioral reality.

The critique of social media-driven commentary is also well-founded. Detailed research gets ignored while surface-level takes go viral. Contrarian positions that require years to mature are punished long before they can prove themselves. This dynamic has intensified dramatically in recent years and makes patient, fundamental investing increasingly difficult when every position is public knowledge.

Where We Disagree With Burry

Not all transparency creates equal pressure. Quarterly 13F filings, the primary U.S. disclosure requirement, impose far less scrutiny than weekly or monthly full-portfolio transparency. Several legendary investors have compounded at over 20% annually for decades while operating under relatively open disclosure frameworks. Warren Buffett and Berkshire Hathaway represent the most prominent example, but they’re not alone.

The claim that private managers routinely achieve 50% annualized returns also deserves scrutiny. While privacy certainly helps, sustaining that level of performance over long periods remains extraordinarily rare even among private investors. Outside a handful of extreme outliers like Medallion, most private portfolios don’t achieve this consistently. Survivorship bias obscures the many who tried and failed, and scaling constraints eventually limit even the most talented. Medallion itself recognized this reality, closing to outside capital and strictly capping assets under management to preserve its edge.

Overall

The argument is directionally correct and explains a real structural disadvantage for transparent fundamental investors today. The social-media amplification of shallow criticism has made it worse than ever. The highest sustained returns have almost always come from managers who could operate with patience and privacy. That said, exceptional compounding is still possible with transparency if you have the right investor base and temperament, though it is undeniably harder.